Dr. Ellen Barnett Updates Us on Imagine You’s Spanish Translation Project

9 min read. Dr. Cynthia Calmenson of IMCF gives an extensive description of their Imagine You program, along with an update on their progress.

(IMCF) began developing a Spanish-language version of their acclaimed Imagine You program, supported by a $50,000 grant from the Healthcare Foundation.

Imagine You is a methodology created by Dr. Ellen Barnett, MD, PhD, geared to improving the personal capacity of providers and clients for addressing health goals. IMCF has been teaching the Imagine You program since 2012 to diverse populations including foster youth, homeless shelter workers, and low-income Latine parents.

Moreover, since the wildfires in 2017 and after, Imagine You training has supported second responders—social service provider staff, disaster case managers, clergy, and volunteers—in promoting resilience among those impacted by the disasters.

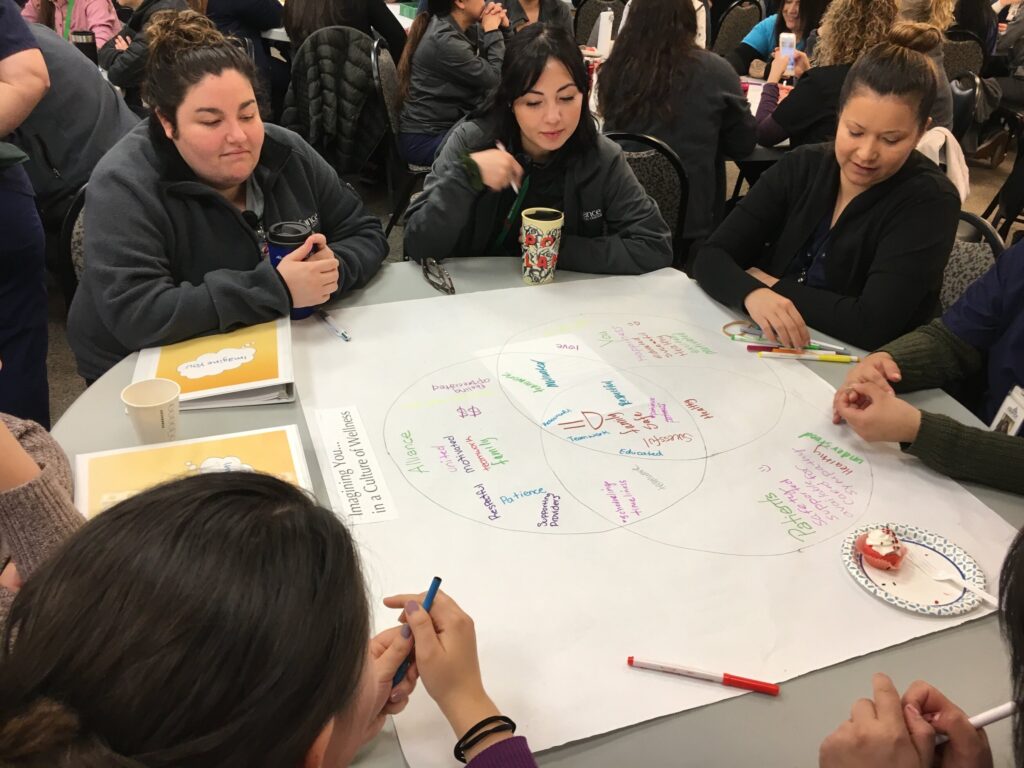

The grant from the Healthcare Foundation underwrote an effort that was about more than merely translating materials into Spanish. The project involved working with cohorts of frontline bilingual and monolingual staff across three local nonprofit agencies providing mental health and wellness services: the Botanical Bus, Corazón Healdsburg, and La Familia Sana.

As IMCF Executive Director Cynthia Calmenson explained at the outset of the grant period:

In the social services and healthcare sector, there are many Latinx staff and volunteers, and yet we’ve always delivered our program in English because that’s what we had to work with. This funding is giving us the opportunity not just to translate our work but to make it culturally responsive. On our team we have three bilingual trainers—Claudia Leiva, Marie Rivera, and Isabel Tiemann—who are all from the social services sector. They’re also passionate educators dedicated to their community. These trainers are very well versed in our program in English and now they’re helping us adapt it, translate it, and deliver it to a Spanish-speaking audience.

Recently, we had the opportunity to speak with Dr. Barnett, now a retired family physician but still very much involved in the work of Imagine You, about the origins of the program and how the Spanish-language translation project continues to inform Imagine You’s structure as a whole. (The following conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.)

What was that moment when you realized something like Imagine You was necessary?

It’s interesting you use the word moment because that’s been one of the throughlines of my life, paying attention to those moments. It started with a personal insight. I was on a journey bringing more exercise into my life, for my health. And I don’t like exercise. I was on the treadmill at the gym and thinking, ‘What’s going to keep me on this treadmill? Because this is not fun.’ And an image came to my mind of me, sometime in the future (my children were teenagers at the time) when I might have grandchildren. I wanted to be able to roll on the floor with my grandkids. So I used that image to keep me on the treadmill a little longer each time.

Later, with my patients, I realized I was feeling frustrated by the traditional medical model of, “I know what would improve your health so let’s talk about that.” I wasn’t getting very far. I had one patient who I had a very good relationship with and, one day, in all honesty in a moment of frustration, I’m not particularly proud of this, I said, ‘Well, why should your diabetes be better? What’s it going to get you?’ She teared up and said, ‘I can’t fly fish with my husband. I don’t feel safe walking in the river because I can’t feel the rocks, because of my diabetic neuropathy.’ I thought, ‘Ah, we finally have something that we can work with together as a goal. Not your blood sugar, not your exercise program—all that stuff will come—but here’s a vision that you have for yourself that I understand, that gives us a common point of focus.’ After that experience, I started asking many of my patients, in different ways, that same question.

To be frank, the doctor visit is not a particularly good place for that. I happened to have had a little bit more time with my patients because I was in a private practice. But even so, we had too much to get through, and too much to get done. Through IMCF we started working with nonprofit agencies in Sonoma County, which is a better setting. People are there because they want something that that agency offers. It’s much more from their own perspective. So we developed a program, really out in the community, with nonprofit organizations.

Was the luxury of time with the patient or client the main advantage?

A little, but it’s more about trust. There’s trust and there’s not so much of a power differential. So it was a better place to develop the tools.

What time frame are we talking about?

It was about 15 years ago when we started that, a little less. In 2010, I was teaching a class that IMCF developed at Sonoma State to train laypeople to be patient navigators, to help patients go through the healthcare system. A fair chunk of the content from Imagine You came from that program. The first Patient Navigator cohort at SSU was in 2010, and we did that for five years. So there was an overlap of a couple of years when we developed Imagine You as the SSU program was winding down.

Did Imagine You always have patient navigation in mind? Who was it intended for?

That was our initial goal—to make an impact in the very broken healthcare sector. In the aftermath of the Tubbs Fire [2017], we worked with disaster case managers who were helping families who had lost their homes. We continue that focus. We’re now coming back to the health services world and particularly community health workers—although there’s a significant overlap, of course, with that disaster relief work.

Imagine You trains the people on the frontlines.

Yes, we work with second responders and others, working in long-term disaster recovery in Northern and Central California.

What tools were they lacking that Imagine You is providing?

That’s a great question, and I have about 14 different doors I could come to that answer through. Primarily, we jumped into this area because of our experience here in Sonoma County. IMCF was part of ROC, Rebuilding Our Community Sonoma County, which was a group that got together after the Tubbs Fire to look at what the community needed. We started participating in that, and it was clear that the second responders were secondarily traumatized by their work. Many of them were also survivors, who had lost their homes. Now they are working with families who lost their homes. There’s a double layer of trauma for those individuals. The second responders were sitting across from people who had nothing and they had very little to offer them. They could offer tremendous personal support, but when your house burns down and you don’t have good enough insurance, there’s nothing that is on the table for you. There are resources around to help you get through the day, and that’s what they were offering. But it was (and is) very difficult to sit there as a second responder with someone who was in that position—and you might be in that very same position yourself.

Through that experience, we realized that what our tools do is what we call “both and”: They’re both for the individual who’s doing the work and they’re tools that they can use with their clients at an appropriate time. They’re small tools. They’re short. They take somewhere between three seconds and five minutes to implement. And they’re woven into all the other tools that second responders are trained to use—the long list of resources, the long list of phone numbers to call, the long to-do list that you have in order to get through that situation. They’re interwoven to make those actions more effective, more efficient, more of service as well to the second responders themselves.

How large is the toolkit?

There are ten modules in the toolkit. We see a variety of responses to the tools, with each trainee gravitating towards the ones they resonate with. As they begin to use them, they find out how they work, how they feel about them, and what the effect is for their clients. It’s a very slow, gentle process of getting comfortable with asking people some different questions or working with someone in a different way.

“Part of our training is about taking a breath, stopping, and listening. It’s a huge ask because of this pressure to want to help the client. . . . But, in fact, that’s not how change happens. Change comes from within. So the question becomes, ‘How do we honor and bring forth those internal feelings and goals, those internal issues, from the client?'”

Ellen Barnett, M.D., Ph.D., Integrative Medical Clinic Foundation

Are these tools geared to what you were describing earlier, mutual recognition and visualization of specific goals?

Some of them do that, yes. But the underlying theme is more about, ‘How can I offer something to you that is from your perspective, not my perspective?’ It’s about slowly bringing forth the elements of the situation that are important to that client, not to the service provider. Because as service providers we know exactly what you need. I’ve got that down pat. My patients frequently told me what they thought I wanted them to say. Because the second responders are good at their job and have such empathy and such commitment to their clients, the tendency is to tell the client what they need. It’s a powerful drive. So part of our training is about taking a breath, stopping, and listening. It’s a huge ask because of this pressure to want to help the client. If you know what they need, of course you’d want to put that out there. But, in fact, that’s not how change happens. Change comes from within. So the question becomes, ‘How do we honor and bring forth those internal feelings and goals, those internal issues, from the client?’

In other words, the client needs to be engaged in the work of finding a way forward?

Yes. Although, at the same time, they don’t have to be. They may not be ready to do that at this moment in time. It’s an opportunity. We know from research that people never, I mean never, change because you told them to. They change because they’ve touched something in their own world that makes them ready to take a step forward. All the information dissemination posters, handouts, booklets, all that stuff has been shown to be pretty ineffective without some sort of engagement process that brings the client along.

How have you gauged the success or effectiveness of Imagine You?

In several ways. Our work is based on tools that have been shown in evidence-based research—and there’s criteria for that label—to affect different outcomes. For example, there’s a lot of research in sports medicine that visualization helps you achieve a goal. In developing Imagine You, I looked at research from many different populations to understand what elements will help me be confident that our program will achieve our goals. That’s called an “evidence-informed” program. Evidence-based research is normally done at universities with big university research programs. I don’t have the resources to do the kind of research that it would take to qualify as “evidence-based” on my outcomes. That restricts us because some places, like Federally Qualified Health Centers, require that you have evidence-based interventions in your toolbox.

So what kind of evidence do we have? The most powerful evidence comes from stories. I’ll give you an example of one. A disaster case manager up in Mendocino County, who had been working with families in various traumatic situations for 20 years, told us as part of our follow-up to the training that the first thing she had asked every one of her clients was, “What do you need and how can I help you?” After the Imagine You training, her first question is now, “What matters most to you in your life?” What she realized was that when she asks that question, her clients don’t have to work at all, they know exactly what matters most to them. Often it’s family but sometimes it’s other things. When she asked, “What do you need and how can I help?”—that’s a job. They’ve got to figure that out. It’s an important question, but asking what matters to them lets her start with something that’s totally from them and not this job they have to figure out. That has shifted her work significantly with her clients. And that’s exactly the point. How can we make it easier and easier for you as a provider to bring forth what’s core to this client or patient in a way that works for both of you?

The other data we have is, you know, how many people would recommend this training to their peers, how many times have you used these tools? We ask those questions, and collect that data as well.

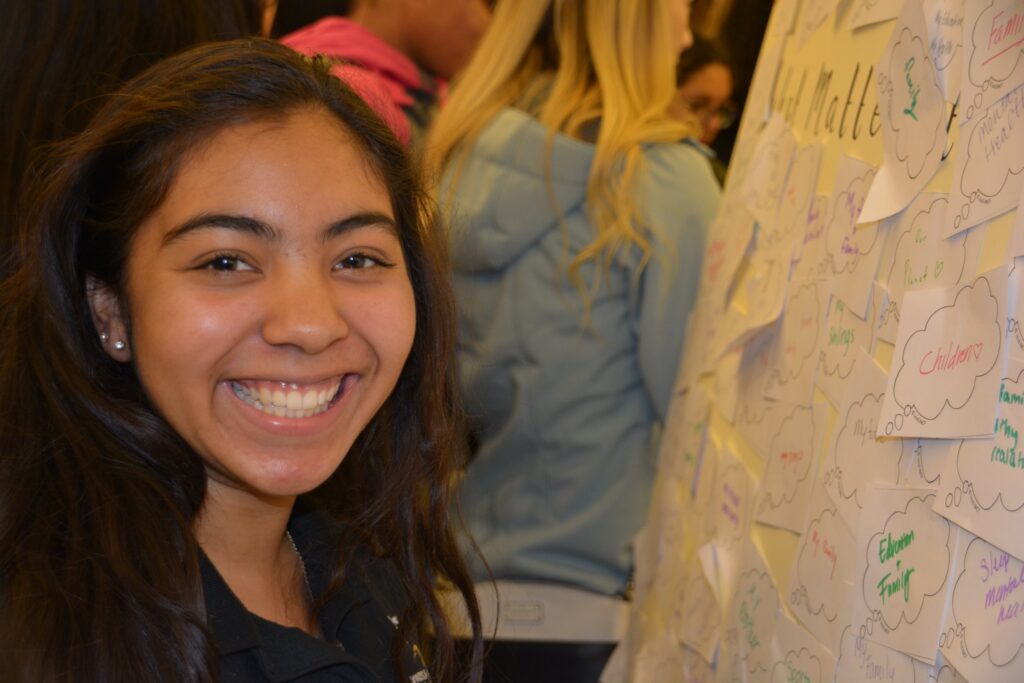

What was the impetus for the Spanish-language version of the program?

The real push for this came from our executive director, Cynthia Calmenson, who was responding to a number of inputs. Claudia Leiva, one of our earliest trainers and now also a member of the IMCF Board, had suggested we create a Spanish-language version of the Imagine You curriculum. Claudia is bilingual and very connected to the local Spanish-speaking community. She was aware of a recurring situation: If you’re listening to something in a language that’s not your first language, you have to do your own internal translation in real time. If you’re bilingual you can do this, but it’s an effort.

At the same time, after the recent fires and the pandemic, there was a tremendous amount of local activism among Latine residents which highlighted the weaknesses in the County’s response to some of the most vulnerable communities, farmworkers as well as undocumented families that couldn’t access resources. There were many organizations that were wonderful in bringing all this to everyone’s attention, so it became known in the nonprofit community. Additionally, efforts around trauma-informed care and the work that started in San Diego as ACEs, the impact of Adverse Childhood Experiences and their impact on health—all of these things were around or came together right at that time.

Cynthia led this effort to offer Imagine You in Spanish. Then we began to get feedback from Claudia and others that, while it was in Spanish, it was not necessarily culturally appropriate. We knew we had to figure that out. So Cynthia applied for the grant to not just translate the program’s materials but to test it out with monolingual learners, to find out what the cultural implications are and the cultural adaptations that are needed.

We knew it would be a challenge because there’s no one culture but many different cultures in the Spanish-speaking community. We got the grant, and we identified three cohorts from nonprofit organizations that have both bilingual and monolingual staff to work with their clients. Then we let the trainers loose. We said, OK, use the translated curriculum but do it your own way. We found we learned more when our trainers had more freedom. We’ve incorporated much of their approach into the English-language version, so it’s been a lovely full circle of learning from that work.

What is an example of something that was discovered in the process?

The most significant is that the original curriculum as developed was quite scripted, and we trained to a script. Our bilingual trainers took a different approach to the curriculum, which worked well. We discovered that giving our trainers much more flexibility in how they present the material, while still keeping to the core elements that inevitably get presented and discussed, was beneficial and it is the major thing that we’re incorporating back into the English version of the curriculum.

How important was the grant for achieving the goals of this project?

Oh, it was critically important. I mean, it was the reason we could do the project. It went well beyond translation into Spanish. The grant allowed us to have the experience of giving the training and refining it, changing it based on the experience of delivering the tools to three different cohorts, a mix in each cohort of bilingual and monolingual staff.

It sounds like having that flexibility to trust the process was key?

Yes! That’s the model for the program itself. What we learned was, ‘First be quiet and just listen.’ Which is the hardest thing to do. The Healthcare Foundation grant supported our approach. We didn’t know what was going to come out of it, but we trust our own process, and that’s the beauty of it. Listening is first and foremost.

Related News + Stories

Invest in Our Community

Your support is vital to our collective vision of eliminating health inequities in northern Sonoma County.

Donate